Monday, December 27, 2004

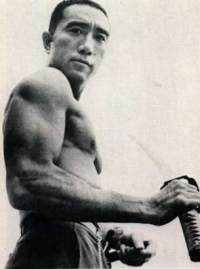

With meathooks like those, it has to be true!

This week I'm reading Mishima's commentary on the Hagakure 「葉隠れ」 (the 'secret' book penned in the 18th century by Jocho Yamamoto) titled 'The Saurai Ethic and Modern Japan'. Mishima wrote this commentary a few years before his suicide, and many see this as his extended suicide note. I am not that concerned about the stardom of his life, or the sensationalism surrounding his demise. The spiritual and philosophical underpinnings are what I'm after.

His observations are a superb foil to some of the 'Nihonjinron' writings that I've recently been exposed to on Japan by non-Japanese (you know who you are). In a nutshell, I think there are two Japans: one that is often debated about with much sound and fury, and another Japan that even its own society has tried to repress. These are the ideas of the Hagakure, and for the majority of 'gaijin' and modern Japanese as well, they still remain, as the title implies, 'hidden under the leaves'. Mishima turns these fallen leaves over only with the utmost of caution in his commentary.

Furthermore, his ideas resonate deeply with some of the inklings that I've been having for a while about this country. I have read most of the major works of the giants of modern Japan literature, as well as their essays, and none of them stands out more than Mishima (although Kenzaburo Oe will always be up there in my top five). This is especially true in Mishima's later writings, where the content is a wild socio-spiritial agitprop cum megalomania. Anyway, a few passages were quite striking, and I'd like to share a few of them with you today. Looking forward to hearing from anyone out there interested in discussing these ideas.

(NOTE: The following passages were translated by Kathryn Sparling.)

Mishima on 'Slow Life'

Ours is an age in which everything is based on the premise that it is best to live as long as possible. The average life span has become the longest in history, and a monotonous plan for humanity unrolls before us. The youth's enthusiasm for "my-home-ism" lasts as long as he is struggling to find his own little nest. All there is is the retirement money clicked up in rows on the abacus, and the peaceful, boring life of impotent old age. This image is constantly in the shadow of the welfare state, threatening the hearts of mankind. In the Scandinavian countries, the need to work has by now disappeared, and there is no more worry over support in old age; in their boredom and disillusionment at being ordered by society simply to "rest," an extraordinary number of old people commit suicide...

In modern society the meaning of death is constantly being forgotten. No, it is not forgotten; rather, the subject is avoided. Rilke has said that the death of man has become smaller. The death of a man is now nothing more than an individual dying grandly in a hard hospital bed, an item to be disposed of as quickly as possible. And all around us is the ceaseless "traffic war," which is reputed to have claimed more victims than the Sino-Japanese War, and the fragility of human life is now as it has ever been. We simply do not like to speak about death. We do not like to extract from death its beneficial elements and try to put them to work for us. We always try to direct our gaze toward the bright landmark, the forward-facing landmark, the landmark of life. And we try our best not to refer to the power by which death gradually eats away our lives. This outlook indicates a process by which our rational humanism, while constantly performing the function of turning the eyes of modern man toward the brightness of freedom and progress, wipes the problem of death from the level of consciousness, pushing it deeper and deeper into the subconscious, turning the death impuse by this repression to an ever more dangerous, explosive, ever more concentrated, inner-directed impulse, We are ingoring the fact that bringing death to the level of consciousness is an important element of mental health.

Mishima on 'Ideal Love'

The art of romantic love as practiced in America involves declaring oneself, pressing one's suit, and making the catch. The energy generated by love is never allowed to build up within but is constantly radiated outward. But paradoxically, the voltage of love is dissipated the instant it is transmitted. Contemporary youth are richly blessed with opportunities for romantic and sexual adventure that former generations would never have dreamed of. But at the same time, what lurks in the hearts of modern youth is the demise of what we know as romantic love. When romantic love generated in the heart proceeds along a straight path and repeats over and over again the process of achieving its goal and in that instant ceasing to exist, then the inability to love and the death of passions (a phenomenon peculiar to the modern age) is within sight. It is fair to say that this is the main reason that young people today are tormented by contradictions concerning the problem of romantic love.

Until the war, youth were able to distinguish neatly between romantic love and sexual desire, and they lived quite reasonably with both. When they entered the university, their upperclassmen took them to the brothels and taught them how to satify their desire, but they dared not lay a hand on the women they truly loved.

Thus love in prewar Japan, while it was based on a sacrifice in the form of prositiution, on the other hand preserved the old "puritanical" tradition. Once we accept the existence of romantic love, we must also accept the fact that men must have in a separate place the sacrificial object with which to satify their carnal desires. Without such an outlet, true love cannot exist. Such is the tragic physiology of the human male.

Mishima on Japanese 「飲み会」

In Japan there is a strange convention by which ordinary human beings strip themselves of their dignity when they drink, exposing their weaknesses and baring their hearts, confessing the most embarrassing secrets. No matter how they grumble or whine, they are completely forgiven on the excuse that they have been drinking. I do not know how many bars there are in Shinjuku, but in that overwhelming number of bars "salary men" sit and drink and complain about women and their bosses. The bar becomes a small, miserable, secret-revealing place protected by the tacit mutual promise that in the morning, although they have not actually forgotten, they will pretend to have forgotten the unmanly, sloppy confessions exchanged among friends the night before.

Mishima on the 'Philosophy of Love' in Japan

The Japanese have a particular tradition concerning romantic love and have developed a special concept of romance 「恋愛」. In old Japan there existed a kind of passion with sexual overtones 「恋」 but no love 「愛」. In the West from the age of the Greeks a distinction was made between eros (love) and agape (the love of God for mankind). Eros began as a concept of carnal desire but, gradually transcending this meaning, it entered the realm of 'idea' (the highest concept addained through reason), where it was perfected in the philosophy of Plato. Agape is a spiritual love completely divorced from carnal desire, and it is agape that was introduced later as Christian love.

Mishima on 'Social Tolerance'

...a philosophy of conscious oversight has always lived in the hearts of the Japanese, at once contradicting and reinforcing their punctilious, cremonious frugality. Nowadays the proper bounds of overlooking and not hearing have been overstepped, and pretending not to notice has taken precedence over economy, resulting in a moral decay sometimes referred to as "the black fog." That is not tolerance; it is merely laxity. Only when they are founded on strict rules of morality can overlooking and pretending not to hear qualify as human virtues; when these morals have collapsed, overlooking and not hearing may become inhuman vices.